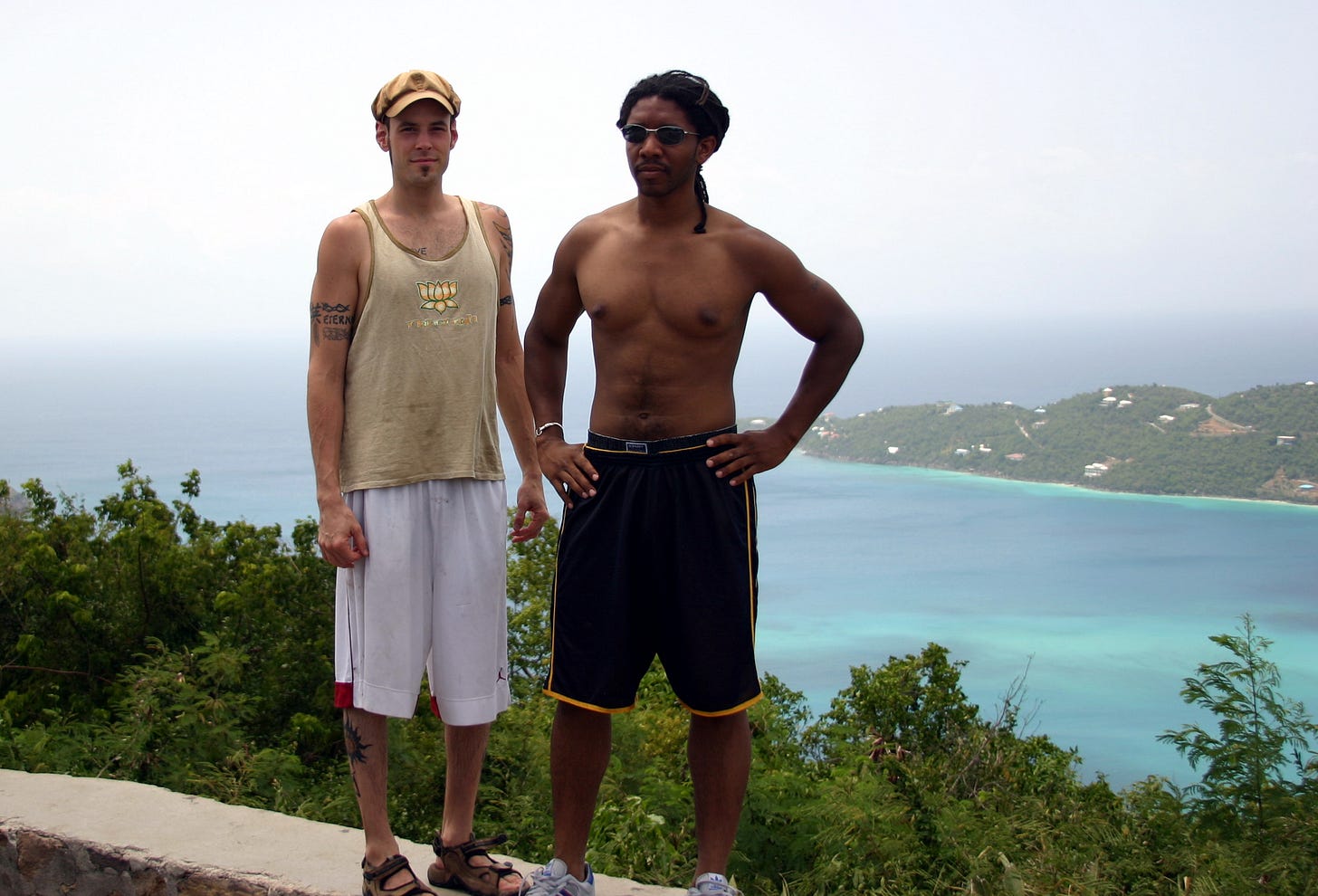

When I heard Daunte Wright was pulled over for having an air freshener hanging from his rearview mirror, it brought back memories. In 2006, Dax and I were pulled over twice within a few miles of each other due to a Vanillaroma air freshener dangling from his rearview mirror. A few years later, we co-published a collection of essays. The following, written by Dax, is based on our experiences driving together. That was not the only time we were pulled over for…being friends. Thankfully, none of our encounters ended in tragedy, but we’ve both had guns pointed at our faces simply for being together. And here we are, 15 years later…

VANILLAROMA

An Outrageous Tale of Air-Fresheners, Terror and Racial Profiling Run Amuck

“I think you think that I’ve lost my mind”

Preachermann, “Negroes Stay Crunchy in Milk”

Just before a cop flicks on his lights and officially informs you that he’s pulling you over, there’s this moment when you know that he knows that you know what’s about to happen. You’re wondering what you might’ve done, if you’re clean, if all of your paperwork is in order. Then you’re wondering what’s taking the son of a bitch so long to make his move. Maybe he’s running your plates. Maybe he’s waiting for you to make a mistake so he’ll have a pretense to pull you over. Maybe he’s searching his statutory memory bank for a legitimate enough rationale, one that a judge will give the benefit of the doubt to should it come to that. Whatever he’s doing, once he’s decided he’s had enough of the cat and mouse game, he pounces.

If it appears as though I’ve been through the racial profiling routine a thousand times, it’s because I have. People tend not to believe me when I tell them that every year of my life since age 16 I’ve been profiled by the police. I’m 31 now and every time I think I’m about to age out of the young black male demographic, I get reminded that there’s no aging out of skin color in America. I’m going to be black until the day I die, and at the rate things are going, there’s always going to be a suburban cop or two – some genius cowboy – who in his brilliance will see my dreads, my seat leaned back a little and my chin a smidgen too high, and conclude that I have no rights, or at least not any that he’ll respect. He can follow me for no reason, pull me over for no reason, hold me until he’s run my license in each of the 50 states, Canada and the European Union, write me as many tickets as he needs to fill his daily quota, and maybe even haul my ass into jail, depending on when his shift is over.

This isn’t a joke, so if you’re laughing, snickering – basically doing anything other than wondering what I’m about to tell you next – stop. It’s not funny that since the age of 16 I’ve been subjected to what amounts to a low-level form of terror on an annual basis, sometimes, if I’m having a particularly unlucky year, semi-annually.

This isn’t another petit-bourgeois negro’s lament over the time he was pulled over while driving his BMW through his suburban neighborhood either. Nor an over-the-top scene from a Hollywood drama. What happened to me today was not simply another “driving while black” occurrence. As a seasoned veteran of the New Jersey thoroughfares, I know the difference between being pulled over “for just cause,” and being pulled over just cause. There’ve been times when I was speeding, times when I’ve had a busted taillight, when I was on my cell phone or driving without my seatbelt on. I readily acknowledge my screw-ups. This was just cause.

Twice. That’s how many times I was pulled over this afternoon. Once in Paramus. Once in Upper Saddle River. Both times on Route 17 heading North to Ramapo, where I go hiking several times a year. But that’s not all. Not even the half. The stops happened less than 10 minutes apart. Literally. I know what you’re thinking: I must’ve done something wrong. Cops don’t just pull black guys over for no reason in 2006. They’ve had sensitivity training, cultural awareness workshops. The state of New Jersey ran a study on racial profiling just a few years ago. Wasn’t the New York Times article about the “suppressed” D.O.J. report that revealed, again, that racial profiling was alive and well handed out at the weekly meeting? Surely these guys have black friends, blacks they work with or live near, don’t they?

Maybe. Maybe not.

All I know is this: a trip that usually takes 40 minutes tops took close to two hours, and it wasn’t because I stopped to use the bathroom. It took that long because I was sitting on the side of the road on two separate occasions, the first time in disgust and the second in utter dismay. How could this happen? All I wanted to do was hike. Just go out into the woods with my buddy Derek and get lost in the world for a couple of hours. It’s an annual ritual we’ve been practicing since college. Go to Ramapo Park. Climb to the top of the mountain. Look southeast and there, across the valley, lies the Manhattan skyline. So distant and so near. The clean air opening up the lungs, offering perspective.

All I know is this: In the last eight years, Derek and I have been pulled over together four times. That’s once every two years, the last time at my wedding! The day before in fact. The night of the freakin’ pre-wedding party. While the party was going on. A hundred or so people at my in-laws’ house waiting for me to show up and I’m handcuffed in the backseat of a police car because the officer didn’t appreciate my attitude. After a half-hour tour of St. Thomas courtesy of the island’s finest, I was driven to a Foot Locker parking lot, where the cop bought a pair of sneakers then dispatched me, though not before advising me to check my New York swagger at the terminal. She could’ve locked me under the jail had she been so inclined, or simply shot me in the face (which on more than one occasion she made it clearly known was her desire). You can’t make this kind of stuff up, I swear. (Incidentally, the very next summer two New Yorkers on the island were discovered dead. The murderers were never found).

St Thomas, 2004

The most memorable Derek and Dax episode to date, however, had to have been the one where I was sitting at a red light on 125th and Broadway in broad daylight when I looked over and saw a gun pointed at my head.

“Get out of the vehicle,” the holder of the firearm shouts.

He’s a white guy with a Tom Selleck mustache and shades. He’s wearing civilian gear and yelling at me like I’m Public Enemy Number One. Behind him sits a jumpout van. The side door’s been slid open and out are jumping a couple of other Tom Selleck types. They check the backseat, front seats, glove compartment, trunk, me, Derek. Jesus, Mary, and Joseph. Nothing. They get back in their van and they’re off. I’m left standing on the street wondering what just happened and why I already know there’s nothing I can do about it.

Maybe it’s because Derek is white and I’m black. Maybe it’s because he’s got tattoos and I’ve got dreads and we just don’t look like we should be hanging out together unless it’s to engage in some kind of illicit activity.

“Where are you two headed?” cop number one asks.

“Ramapo,” I say.

“What, there a barbecue or something going on?”

A barbecue, huh? With watermelon, Kool-Aid and fried chicken. You racist prick.

“No officer. We’re going hiking. We go every year.”

“Oh yeah? Where to?”

I just told you!

“Ramapo,” Derek says.

“Mind telling me why you pulled me over officer?”

“We’ll get to that. Can I have your license and registration and insurance?”

“Your registration up to date? Your insurance?”

“Yes. Everything is in order.”

After the standard wait period, he returns to the window. I look up at him and see a guy in his early thirties. A guy swelling around the middle. A guy who used to play high school baseball. Outfielder. Decent set of hands, decent wheels: nothing special. But I also see a human. He doesn’t want to throw the book at me. He knows what he’s doing is dead wrong, that the only reason he pulled me over was because he had to write some tickets on the holiday weekend and, well, it’s just easier to write them to me. It was, at least.

He calls me out of the car, around to the back and he tells me to be straight up with him. There I am with my Rasta hat, beard growing wooly and a tattoo fanatic in my passenger seat.

“You know you got a warrant in Jersey City,” he says to me.

I know all about the warrant. Knew it was only a matter of time until I had to face it. Here’s the story officer, I say, and hear myself slip into the art-of-persuasion mode.

I tell him about the August night a year ago when I was coming back from a fundraiser for a friend. I tell him how I ran directly into a DUI checkpoint and how, without even flinching, the cop at the head of the line looks up and tells me to pull over. I tell him how it wasn’t a surprise, how I’d even told my buddy Jeremy (who was my passenger that time) that I was going to get pulled over. After you’ve been profiled for nearly half your life you’re able to see these things before they happen. They held me for 20 minutes, wrote me three bogus tickets – one for not wearing a seatbelt that I took off in order to retrieve the registration – then sent the notices to the wrong address. When I called to let them know (“Hey geniuses, you sent the court documents to the wrong address”), I was informed a warrant had already been issued. If I wanted to fight the case I had to put up $2,000 bail. If I just want to pay the fines I had to hand over $750.

Why didn’t I just pay it? Why not just make my life easier and give them what they want? Because it never stops. The kicking never stops. The singling out never stops. Frankly, I couldn’t just hand the state money for bogus tickets. I’ve been doing it for too many years. The thought alone sickens me. It offends every jurisprudential bone in my body. It transgresses every notion I have of a decent country where people aren’t extorted by their government. Housewives in their SUVs don’t have to deal with this. Businessmen in their luxury sedans don’t. Attractive young women in their Honda Civics don’t. Old people in their Grand Marquis don’t. Just guys like me. Guys that no one sympathizes with anyway. Guys that, in a court of law, most judges won’t believe. Screw it if I went to law school myself if I passed their stinking bar exam on the first try. People ask me why I never practiced. Here’s why: I could never uphold a law that doesn’t even respect me or anyone like me.

At the end of my spiel, I have the cop as much on my side as he can be and not feel like he’s piercing the blue wall.

“What’s the story with your friend?” he asks. He means Derek. The implication is obvious: he looks like some kind of hippie.

“He’s an author, a musician, a yoga teacher. He’s a brilliant human being.”

“He teaches yoga?”

“Yes, officer, he does.”

“So why all the air fresheners?”

“The what?”

“The air fresheners in the car. Why so many?”

Is this why you’ve stopped me? Why we’re standing on the side of the road in the middle of the day on the Fourth of July weekend? Please, tell me there’s more.

“It’s my wife. She likes them. Vanillaroma. She puts new ones up and doesn’t take the old ones down.”

“So if I go in your car I’m not going to find anything?”

First of all, you have no cause to search the vehicle. I’ve displayed no impairment. You didn’t smell anything. What are you basing the assumption that you will find drugs in the vehicle on? Besides, of course, my dreads and Derek’s tattoos.

“Officer, we just want to go hiking. That’s all. It’s Sunday and I want to enjoy the day.”

Turns out there’s a loophole in the law. Since I still have a New York State license, there isn’t a Jersey license to suspend. Legally I can still drive in New Jersey. The cop tells me this, but I already knew. It’s the reason I didn’t give up my New York license in the first place. I’m no dummy. I let him go on anyway because it makes him feel better. He can think he’s done a good deed today. He let a black guy and his hippie friend off. He could’ve been a jerk, but he decided, perhaps in the spirit of Independence, to let me go.

I reach my hand out. “Thank you, officer.”

He hesitates. This whole situation has disoriented him. He was expecting me to be full of indignation and I was calm, cool – a guy he could sit at a bar and talk about the Knicks’ awful draft picks with. At last, after thinking better of it, he gives me his hand.

No way this is happening. Not a second time. Not so quickly. How is this possible? How is it not some kind of record? How can anyone look at me with a straight face and tell me I’m just being paranoid when I look out of the rearview mirror every time a cop car passes me. Low-level terror, I tell you. At sixteen, the very first time I get the car, I get pulled over. At seventeen, I get a revolver shoved into my throat. This stuff stays with you, marks you.

The Upper Saddle River cop couldn’t have been more than twenty-six, twenty-seven. A boy’s face and skinny forearms. I still have my license, registration, and insurance in my lap.

Here you go, officer. It’s a good thing I just got pulled over a few miles back. Didn’t have to go rummaging this time. This time everything’s ready for you.

“Mind telling me why you pulled me over?”

“The air fresheners.”

“What about the air fresheners, officer?”

“They’re obstructing your view.”

Excuse me, but shouldn’t I be the judge of that? Can’t I tell if a few fake Christmas trees are impeding my vision field? Besides, officer, how would you have even known this unless you were following me, looking for a reason to pull me over?

I remove the air fresheners. Throw them into the backseat. Foreswear them: from now until the end of time I will never place a Vanillaroma air freshener on my rearview mirror.

“Is that better officer? Does this resolve our problem?”

But it’s too late. Here comes another squad car. And another. And any hope we might’ve had of getting off with a warning vanishes. Rationality out of the window. The mob mentality reigns once again.

“Look guy, I don’t know what your deal is. Maybe you’re a student. I don’t know.”

“I’m an author, actually. I write books. And I’m a lawyer too.”

“I understand. We’re going to try to resolve this as quickly as possible. By the way, do you have $750? Just in case.”

By that he means can I bail myself out of jail if need be? Seems as though the same license that wasn’t suspended in Paramus is suspended in Upper Saddle River. Great. But there’s something in his concern. Some hint of guilt. Why would he care if I could make bail unless he felt bad that he was pulling me over because of my Vanillaroma air fresheners—all seven of them? I feel for him. He’s still new to the force, still learning the ropes. He isn’t a wall of inhumanity yet. The system hasn’t completely broken him down. The moment I told him he was the second cop to pull me over in the last 10 minutes I saw the change in him. He wished he had let me go. He felt awful. He’s not a racist and he wants me to know that. Of all the situations he could find himself in this is the worst. Black guy. Seems to be articulate. Says he’s a lawyer. Doesn’t seem hostile.

Thirty minutes pass. Every so often the cop returns to let me know he’s still waiting to hear back from the dispatcher. I guess their computers aren’t working as fast as Paramus’s, I tell Derek. I take a nap. Change CDs. Directly ahead of me an American flag flaps in the wind. In two days the country will officially be celebrating its independence. Its freedom from British tyranny. The flag flaps and I wonder what I’m supposed to drive away from this with. Where is the opportunity for growth and understanding? Two nights earlier I was telling a friend how much I loved this country. Telling her that there’s no place I’d rather live. It’s just too easy to hate America in 2006. No, I love this poor stumbling, blubbering giant. I love its tragic wounds, just as I pity its inability to win at any world-class sports, and our rabid denial of a declining position in the world. The cops think they’re performing a vital service to the community by harassing people like me. This is what they have been raised to believe, what their fellow officers speak openly about amongst one another. A black guy in Upper Saddle River just isn’t right. It sets off bells in their heads. No way I could lead a life that is possibly beyond their own, wider, broader, deeper. No way I have interests that might carry me out of the city and into nature.

The reality—and I swear this is what I was thinking while I waited to find out if I’d be hauled in or not—is that this is nothing. Yes, it is a form of state-sanctioned terror. Yes, it is a very inconvenient thing to deal with year in and year out. Yes, it is wrong. But I also understand it now. Baldwin says it best in The Fire Next Time: “Please, try to remember that what they believe, as well as what they do and cause you to endure, does not testify to your inferiority but to their inhumanity and fear.”

Sometimes I wonder what the cops would do if I started crying. If I just broke down in tears and begged them to stop picking on me. Would they take pity on me?

“They’d probably think you were crazy,” Derek said.

What it comes down to is this: I still don’t have any rights that this country is bound to respect. Wherever I’m going, whatever I have planned, can at any moment be disrupted. This says nothing of the very legitimate and real threat of violence that someone who is routinely placed in my position has to feel. After all, they have the guns, the mace, the Billy club, the backup, the history. What do I have? Legal recourse? Please.

In the end, the cop gave me two tickets.

“I have to do it,” he said. “I wish it were otherwise, but I just gotta.”

There were other cops, superiors, watching him. He couldn’t allow me to get off. He had to ticket me. Mandatory court date. “But I know the prosecutor. He’s a real good guy. He’s fair. He’ll probably get one of these thrown out of for you. Take care. Have a nice weekend.”

A man in a bind. In over his head. Unwilling to disrupt the status quo, even to do right. All over the country, these are the people wearing badges, holding guns, upholding law: men who feel bad about their actions but who don’t do anything to correct them. Law without ethics.

Photo shoot for our essay collection, Jersey City, 2006

Onward. Cee-Lo screaming, “Maybe I’m crazy” into my eardrums. It never even occurs to us that maybe we should turn around and go back home. That perhaps we should count our blessings and forget about hiking. If Upper Saddle River, one of the wealthiest suburbs in Bergen County, needs my money I’ll give it to them (though not until the last possible minute). That’s all it’s about anyway. It’s not about me breaking the law or them protecting the highways from dangerous motorists. It’s about money: cold hard cash to be placed in their coffers and distributed however some bureaucrat sees fit. This much I accept, however begrudgingly. What I reject is my own anger and cynicism. The bottom line is we all need reminders of the way stuff really is sometimes. A week ago I’m giving a commencement address in front of hundreds of people. Afterward, I’m told how great I am, how much of an inspiration my words were. Today I’m being profiled. What’s new about that? It’s the age-old story of the successful black man in America. One minute we’re on top, the next we’re cosmic slop. If anything, I should feel a little proud to be in the company of every strong black man who’s ever dared to be unapologetically himself in this country.

The key is laughter. Derek and I have to laugh whenever we think about the number of times we’ve been pulled over together. I have to laugh at the absurdity of two different cops pulling me over for having too many Vanillaroma air fresheners.

My hope: that between the two cops, I made at least one lasting impression. Maybe next time they’ll think twice before choosing the easiest target to profile. They’ll wonder if what they’re about to do is grounded in anything other than false pretense. They’ll take into consideration that, just like them, I’m a workingman struggling to keep the weight of this crumbling empire from falling squarely on my shoulders. Being the eternal optimist, I have to look at it this way. I have to believe people can change, that they grow out of their shell of ignorance.

I have to believe that one day the terror will subside.

July 3, 2006