Permission to eat

The danger of restrictive diets

Earlier this week, my reporting on male eating disorders appeared in Teen Vogue. I’ve covered this topic a few times in recent years, and the problem seems to be getting worse. At the very least, it’s not getting any better—at least from what we can tell from limited data.

In Teen Vogue, I mention a few potential reasons for why male eating disorders are underdiagnosed. A big one is presentation: men tend to focus on muscularity while women on thinness. Being ripped is treated as peak fitness in modern culture. While working out is obviously healthy, the eating patterns that accompany some exercise protocols warrant caution.

I believe another related reason is due to the obsessive American focus on “manhood.” (Sure, other cultures have their versions, but I’m sticking to what I know.) Masculinity is often conjoined to muscularity in weightlifting and optimization spaces.

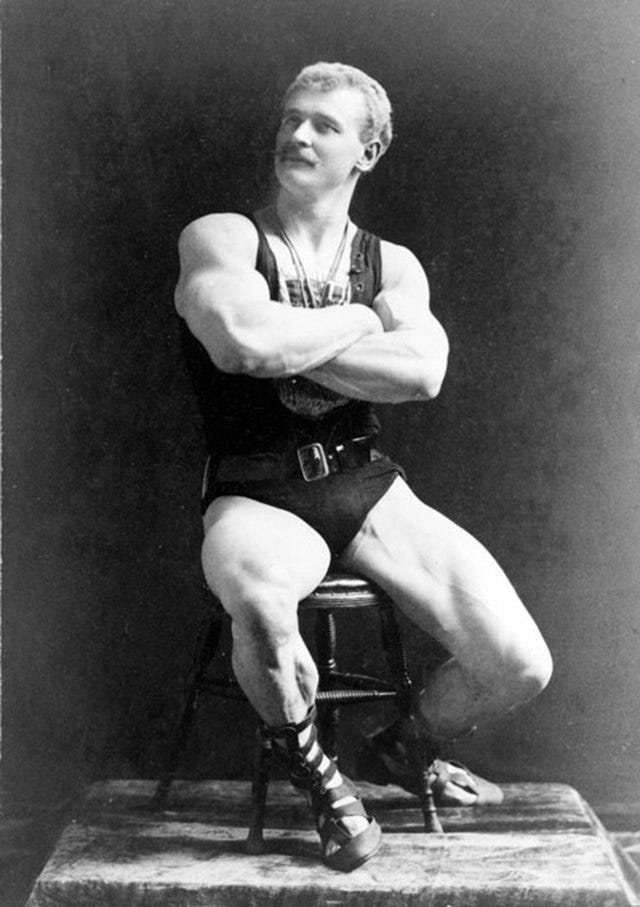

Not a new phenomenon: I remember reading Archie comics back in the eighties with the bulky lifeguard kicking sand on the skinny wimp. Since the late 19th century, ever since Eugen Sandow graced magazine covers, men have been obsessed with size—the more of it, the better. By the seventies they had the means, in the form of steroids, to achieve previously unimagined bulk.

For example, here’s a Hulk Hogan action figure that I owned in 1984, when I was nine years old.

Impressive figure, and pretty true to the actual Hulk Hogan, but honestly not far off from Eugen Sandow, the (very racist) muscular poster boy of the early 20th century.

Now here are some contestants from the 2021 Mr Olympia competition.

You don’t get that body composition without training, dedication, and…a lot of chemical assistance. (I don’t know these men and am not claiming they have eating disorders, to be clear; I’m merely pointing out what boys and men have to contend with when seeing the image of a “strong man” compared to previous generations.)

Nutrition is an important partner to muscularity, though we shouldn’t discount genetics. I grew up overweight—the stimulus for my later battle with an eating disorder. As an adult, getting “shredded” would take an inordinate amount of work given my genetic heritage. Other men work out far less than I do yet have more of a physique. And I know from experience, as well as conversations with other men, that the genetic factor can be daunting.

In fact, the closest I ever came to dropping most body fat required months of intermittent fasting. As I was nearing the physical goal, the emotional toll outweighed everything. I was miserable. I had closed my eating window from noon to 6 pm on a daily basis; by 10 am my body was screaming, especially since I work out daily between 6 and 8 am. I eventually abandoned the physical goal, and have been happier ever since.

Then there was the time I tried the master cleanse, a five-day lemon juice/cayenne/maple syrup-only fast. I nearly collapsed on day four while in the gym in lower Manhattan. I immediately showered and went next door to eat a slice of pizza. After I stopped shaking, I decided to never do non-food fasts again.

Mostly, though, my eating disorder involved an obsessive focus on nutrition labels. I was taken in by The Zone diet, which dictates that you eat 40% carbs, 30% protein, and 30% fats. Forget calorie counting, this involved complex mathematics. Sure, it’s basic arithmetic, but if a meal involves multiple food items, you have to consider the nutrient composition of each source, then combine them. Instead of enjoying meals I would often skip them out of sheer frustration that I couldn’t dial in the right percentage.

Someone once told me that “you’re sick and tired until you’re sick and tired of being sick and tired.” While applicable to a variety of instances, this is certainly how I felt about my obsessive eating habits. Once I stopped worrying about food and just tried to eat well, and not stress out when I didn’t, I felt much healthier.

I’ve always exercised so that wasn’t an issue. But properly fueling my workouts has made me stronger than ever, which is a good place to be at 48 years of age. I’m also aware that my personal nutritional intake—a plant-heavy carnivorous diet, after decades of trying out various fads and diets—is not necessarily appropriate for anyone else, which is why I never offer food advice. All I can say with confidence is that balance matters, and to not discount the pleasure of eating.

I’ll be interviewing Dr Sarah Ballantyne soon about her upcoming book, Nutrivore. When creating a short video based on her work this week, one thing she said really resonated with me: she focuses on permissive dietary structures instead of restrictive dietary structures.

This was the opposite of what happened when I suffered from an eating disorder. I focused so much on what not to eat that I lost all sense of what to eat. Tragically, so much healthism marketed in the wellness world focuses on what led to my eating disorder, and I’m going to guess the same has occurred with many others: by demonizing certain foods or food groups, we miss out on both the nutrients available in those foods as well as the joy of eating them.

That’s simply not a healthy way to live.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to re:frame to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.