In defense of potatoes

How fad diets and misinformation ruined an ideal food

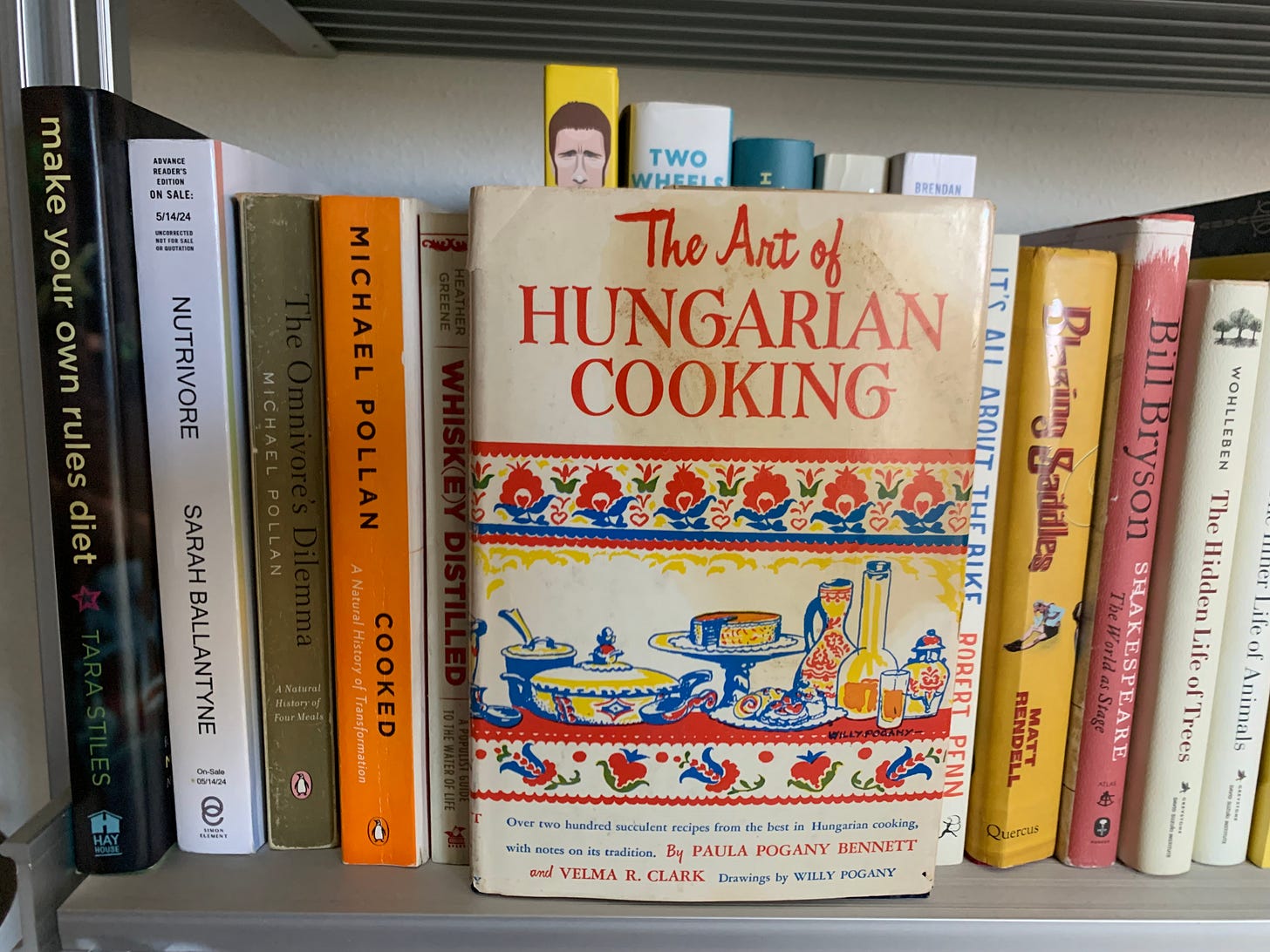

In January, I stumbled upon a copy of The Art of Hungarian Cooking at Mother Focault’s, one of my favorite local bookstores. You’re forgiven if you’re not aware of this 1954 cookbook. Hungarian cuisine isn’t the most well-known culinary tradition.

In fact, when I ask the bookseller how this gem found its way into the stacks, he told me that someone had recently dropped off a giant box of old cookbooks. The next day, a chef was preparing for an installation and bought the entire box—except for The Art of Hungarian Cooking.

One man’s trash…

My wife laughed aloud. As did I. We have an ongoing joke about our respective familial culinary traditions. You can’t walk a stone’s throw in Portland without running into a Thai restaurant, whereas to find a Hungarian restaurant, we have to drive nearly two hours. Turns out that sole establishment in the state of Oregon is only open one day a week.

In truth, all folk cuisine utilizes a limited number of ingredients. Food traditions tend to emerge from the lower classes, where resources are thin and ingenuity is necessary. (These traditions are often then coopted by the upper classes; Béla Bartók proved this with his incredible survey of Hungarian folk music styles, as a parallel example.)

For a variety of geographic and cultural reasons, Asian folk cuisines are rich in spices, giving households a nearly limitless range of flavors to work with. By contrast, Northern and Eastern European cuisines are quite bland. If Hungary is known for anything, it’s paprika, and even that pepper was imported from Mexico in the mid-19th century. (Hungarians took full ownership, however.)

There’s no cuisine I don’t love, save perhaps Nordic cuisines, and that’s only due to an excess of raw onions—and even here I can improvise. That said, I’m a fan of Hungarian cuisine and its extremely limited range of options; I own two newer cookbooks to guide me. Plus, having grown up eating Chicken Paprikash, I can improvise well with that hearty, comforting dish. Goulash holds a special place in my heart as well.

Beyond the reliance on beef and chicken, Hungarian food, like much Eastern European cuisine, loves potatoes. The vegetable grows well in colder climates, and temperate ones as well. I currently have three different spuds in my garden box that are nearing harvest. My wife often remarks that she’s never seen someone with such a love for potatoes and all its various forms as me. It’s true: my upbringing was dominated with every imaginable way to cook and consume potatoes. My favorite dish when I was young was mashed potatoes and corn. They are a near-perfect food.

Yet, as Wired recently reported, Americans are ignoring potatoes in droves. Since the government started tracking data on potato consumption in 1970, we are experiencing an all-time low. Some have even advocated for disowning potato as a vegetable, instead just lumping them in with all the other “junk food” on our shelves.

There are a few reasons for this, but one thing is certain: our growing disdain for this starchy root vegetable is a shame.

Peasant food is the best food

Food trends are unavoidable. I’ve watched a range of foods rise and fall in the zeitgeist over the decades I’ve worked in and reported on the wellness industry.

Take eggs: one day they’re a perfect food, the next a documentary (falsely) claims they’re as harmful as cigarettes. Nuance and balance are rare in wellness food discourse.

The wellness industry infamously demonizes foods. Whereas we know oatmeal is a healthy, affordable meal, people like Dave Asprey will call it “peasant food” in order to monetize his own supplements. (Also: “peasants,” as I mention above, are responsible for the bulk of folk cuisines worldwide.) Seed oils are the current devil in the supplements-slinging influencer downline, despite mountains of evidence of their benefits.

Potatoes are a longstanding target of wellness grifters. Psychiatrist Paul Saladino, who refashioned himself as “Carnivore MD” despite having no nutritional training, recently called French Fries “the single worst food you can eat.” (The man also yells at kale in produce aisles, so take his videos with a grain of salt. Although he likely demonizes salt as well.)

French fries are not the healthiest option for eating potatoes. Nor are potato chips. Despite their popularity—there’s a misperception that French fries are the #1 way Americans consume potatoes—the top two ways we eat potatoes are, in fact, good for us.

Mashed potatoes: 28%

Baked potatoes: 25%

French fries: 20%

Home fries / hash browns: 10%

Plus, the benefits of potatoes are well-documented, as Wired reports:

The white potato is a criminally underrated food. Compared with other carb-loaded staples like pasta, white bread, or rice, potatoes are rich in vitamin C, potassium, and fiber. They’re also surprisingly high in protein. If you hit your daily calorie goal by eating only potatoes, then you’d also exceed your daily goal for protein, which is 56 grams for a man aged 31–50.

Potatoes have been shown to be good for digestive health, bone health, and heart health; lower blood pressure; aid in disease prevention; and are nutrient-rich. Still, due to the recurring low-carb diet trend and the perpetual state of food fear that wellness influencers invoke to keep their audiences purchasing novelty items, Americans peaked at potato consumption in 1996, when we were eating 64 pounds per year.

Today, that number is 45 pounds.

This isn’t an argument to eat more potatoes. You might not like them. Maybe you get those nutrients elsewhere. While widespread throughout a variety of global cuisines—it’s hard to top a spicy Aloo Gobi—not everyone has the same cultural and familial love for the spud as I do.

But it is a suggestion to not get caught up in every food trend that hits the algorithm. It never ceases to amaze me that the same influencers who romanticize the “ancient wisdom” of our ancestors’ health decisions will turn on a dime when the romanticized product doesn’t serve their downline.

The humble potato is easy to demonize when you have no idea what you’re talking about.

That just means more for the rest of us.