“There’s a lot of issues with toxins, whether it’s food or vaccines or chemicals in our homes,” she said. “People focus on these bigger issues because they don’t even see the smaller issues.”

That’s how the Washington Post uncritically featured one MAHA mom in a recent puff piece about shifting demographics in the environmental movement. While the journalist rightfully pointed out that MAHA stans are more focused on individual responses to lifestyle choices than public health solutions, they failed to define “toxin” or assess whether or not these influencers’ citations of toxicity are valid. (They’re not.)

Not everyone is so careless. Dr Jessica Knurick recently broke down how everything in our homes is potentially toxic, rendering MAHA’s selective disregard of toxicity impotent.

Flaccidity is compelling in social media-driven wellness circles, however. Sure, there are real problems of toxic chemicals and an ongoing concern over microplastics to assess. How easily the MAHA mind swerves from supposed toxicity in food additives to household molds to vaccines in the quote above, even as every vaccine must list every tested and regulated ingredient on the packaging (and which you can quickly find online).

That’s what makes RFK Jr’s claim that there are “hundreds” of ingredients in some vaccines and “we” don’t know what’s really in them so laughable: everyone can quickly refute such an absurd claim. You just need the will.

Speaking of will, the WaPo article could have explored MAHA’s naval gazing in depth. While presenting MAHA moms as a “new” movement, the notion that nefarious powers keep us sick and the enlightened are charged to reverse course is reminiscent of the right’s longstanding adaptation of the hero’s journey: only brave truth tellers can set us free. But that freedom isn’t extended to all members of society, for you have to have the time and resources to churn butter and deploy homemade vinegar-based cleaning solutions to stick it to the man.

In reality, the MAHA mindset is just a continuation of post-New Deal conservative thought: your health is yours alone to manage. This self-empowering slogan—take control of your health!—is the perfect way to avoid discussion of socialized medicine.

Conservatives found an ideal audience to parrot their free market beliefs in the wellness community.

MAHA’s Reaganomics

Wellness is an umbrella term that includes a variety of movement, nutritional, and lifestyle practices. Many, like yoga, meditation, and stress-management techniques, bring people relief while helping them feel centered against the vicissitudes of life. Having spent decades of my life as a yoga and fitness instructor, I’ve felt and seen the benefits firsthand.

There’s another side to this industry. I recall yoga teachers telling students “you’re your own best doctor” and “no one is looking out for your health except you” decades ago. The magical promise of food as medicine—a misreading of text from the Hippocratic Corpus—has circulated for generations.

Selling the promise of individual health through the consumption of untested products while lambasting medical professionals at every turn is the consequence of decades of polarizing wellness rhetoric.

No industry benefits more than supplements, which was enabled by the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DHSEA). This legislation lets food companies and dietary supplements manufacturers market and sell supposed health-related products without the burden of scientific research. A tiny asterisk pointing to an even smaller disclaimer on bottles and websites suffices, which consumers are as likely to read as the legalese accompanying phone updates.

Social media gave supplements (and related industries) steroids. Aspiring wellness influencers began using discount codes to generate income for themselves and even more for those companies. There’s nothing inherently wrong with promoting a product you believe in and making a little (sometimes, quite a lot of) cash. But when sales pitches for untested products include health claims, from the rather benign (and predominantly nonsensical) “immune-boosting” to the not-at-all benign “treats cancer,” a whole host of problems emerge.

Here’s one: influencers fighting for eyeballs need to stand out. An entire wellness community, fed language about being their own doctor, is now being told doctors and nurses are involved in a medical conspiracy within the “sick care system.” Kennedy is one of the loudest proponents. Calling FDA employees sock puppets for the deep state during his first official meeting as their leader is but the latest example.

In her book, Doppelganger, author Naomi Klein writes that conspiracy theorists “get the facts wrong but often get the feelings right.” Wellness influencers, like most Americans, feel the weight of living in the only OECD nation that doesn’t offer citizens universal healthcare. Our haphazard, convoluted system means many fall between the cracks. Void of a centralized patient advocacy agency, it also means pharmaceutical companies and hospital systems maximize profit without worry of being challenged. Regardless of what anyone feels about the public execution of a healthcare CEO, few Americans were surprised by the reason for it.

Kennedy, like many wellness activists, taps into a primal rage visceral to many Americans. Instead of using their platforms to fight for universal healthcare, they weaponize that anger against the entire medical system, as if millions of healthcare practitioners and researchers are on the take.

Kennedy has called the idea of universal health care unfair, for in his mind health is a zero sum game: if you put in the work, you deserve the benefits. This is the foundation of Reaganomics health care.

Ronald Reagan’s pro-competition policies encouraged private-sector competition. By deregulating insurance markets and shifting payments to fixed rates per hospital visit, financial risk was transferred from insurers to healthcare providers and, ultimately, patients. Americans were forced to shop around for healthcare services, adding layers of stress and uncertainty, often at a time when we need the opposite.

The 1981 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act replaced categorical federal health programs with block grants, reducing federal oversight and allowing states to tailor health services. This decentralization diminished federal safety nets, placing greater onus on individuals to navigate fragmented local systems.

Reagan also reduced Medicare and Medicaid funding while repealing mental health initiatives, shifting care for vulnerable populations to underfunded community centers. This led to gaps in services and forced individuals to rely on private insurance or out-of-pocket payments.

The most affected? Low-income families, the mentally ill, and elderly populations all faced reduced access to subsidized care, which exacerbated disparities. The administration’s policies assumed individuals could independently manage health costs despite systemic barriers. Sound familiar?

Like Kennedy, Reagan framed healthcare as a matter of individual choice, opposing government "encroachment" through programs like Medicare expansion. His rhetoric positioned reliance on public assistance as a moral failing—just like today’s MAHA activists.

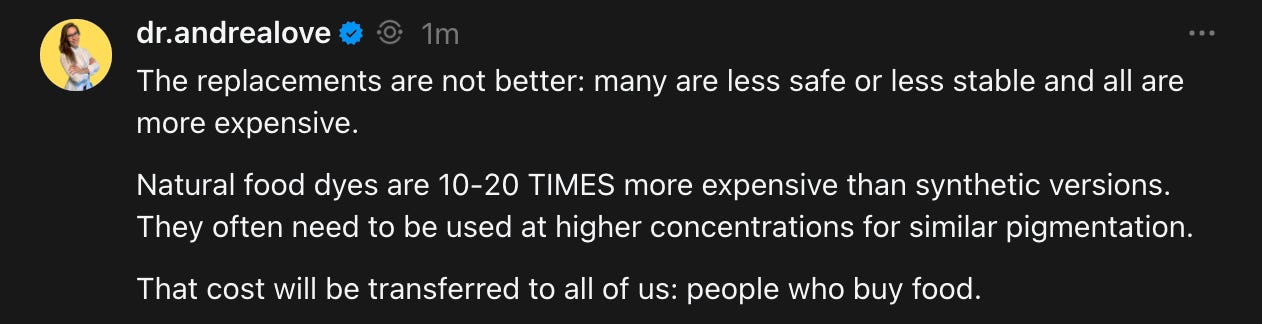

What Kennedy, like indoctrinated wellness influencers, fail to consider is that health is not always an individual choice. Sure, they hint at it with their rage against food companies, but that’s mostly performative: natural food dyes are more expensive and more likely to result in allergic reactions. The real issue with ultra-processed foods is their macronutrient content, not the coloring.

This sleight of hand allows wellness influencers to feel like their activism is doing some major good—at most, taking out some synthetic dyes could be a minor good if it turns children away from high-sugar ultra-processed foods—but they never address the far-reaching systemic effects of the social determinants of health.

The real irony: Kennedy claims that Americans want choice (another longtime conservative code word) in health care, yet he’s up in arms when it comes to the free market in supermarket aisles.

Free market healthcare = good. Free market grocery cart = bad.

This argument makes no sense, yet nothing about MAHA is logical. It’s vibes through and through.

Far from championing health, MAHA activists partake in the same expensive, exclusionary process they decry—and for those on the top of that pyramid, make a killing while doing so.