Nothing about this is normal.

I read this question constantly on social media: What is going on in America?

Of course, there’s much to celebrate about this country. We’ve exported jazz, rock, and hip-hop globally. Hollywood is one of the most influential mediums on the planet, for better and worse. The food isn’t bad, though most of the best is from elsewhere.

Still, we can be inventive.

But y’all aren’t willing to import our strange, erotic fetishizing of guns—and I don’t blame you.

I don’t get it either, but I didn’t grow up with guns, except the BB gun we’d shoot at aluminum cans in our suburban backyard. It wasn’t much different than the silly air pistol that made the doll play piano down the shore.

I don’t take issue with guns because every gun owner I know doesn’t worship them the way that a minority of Americans do. Whether for sport, hunting, collecting, or protection, it’s just something that they do, or own, and that’s the extent of it. I’ve gone out shooting skeet with friends because I like challenges, and I like hanging out with friends. Then I move on with life.

But we’re not moving on. As of today, there have been 278 mass shootings in this country, and we’re not even halfway through 2022.

This isn’t normal.

Where this goes

This warning from mathematician Edward Thorp is worth heeding.

I don’t think we can predict for sure what’s going to happen, but we can map out scenarios. You could have an autocratic country where a minority pretty much rules everything and dictates to everybody else. You could have a turbulent country where a large part of the country, maybe a majority, is badly upset and just wants to bust everything up and start over somehow.

Busting everything up is easy; building it back up is another story, one that requires dedication, planning, and intention. Thorp might broker in advanced mathematics, but basic arithmetic suffices for our road map:

There’s an estimated 120.5 guns per 100 American residents. That’s well over double the next country, Yemen, and nearly triple Serbia and Montenegro.

According to a 2017 Pew poll, only 30% of American adults own a gun. So that 120.5 per 100 number is skewed. In fact, if you divide the 393 million guns in America by the 77.4 million adults who own them, that’s over five guns per gun owner average.

While suicides remain the #1 cause of gun-related deaths, consider another number: 79% of homicides in America are by gun. In Australia, that number is 13%; in the UK, 4%. In Japan—we’ll get there.

In 2016, the gun rights lobby spent $54.9 million, while gun control organizations dropped roughly $3 million. This is in large part why legislation never changes.

Factor in my earlier sentiment: many gun owners possess a gun or two. Like Thorp said, a “minority pretty much rules everything” is a possible outcome—and they will be armed.

Owning a gun isn’t strange. Fetishizing firearms is abnormal—neurotic to the point of serious danger.

But Thorp’s prediction (and he knows this as well) is not inevitable.

In that spirit, let’s look back at an extremely well-armed culture that decided to completely turn its back on guns: 17th-century Japan.

Giving up the gun

In his 1979 book, Giving up the Gun: Japan’s Reversion to the Sword, 1543-1879, the late Dartmouth professor, Noel Perrin, investigates a rare historical moment: an entire country discovering and developing a technology before leaving it behind.

The story begins in 1543, when a Chinese cargo ship docked in a small harbor in southern Japan. While the majority of passengers were Chinese, three Portuguese “adventurers” were on board—and they were armed. This marks the first recorded instance of Europeans setting foot on Japanese soil.

When the travelers decided to shoot at ducks, the locals noticed their strange death machines. The local lord immediately offered them a huge sum of money for the guns, which they accepted.

The Japanese applied the same craftsmanship to guns as with swords. Within a few decades, they became global leaders in gun production. That’s no understatement: at the time, there were 25 million Japanese compared to 7 million Spanish and less than 5 million British.

Seventeen years after those ducks fell from the sky, the Japanese were winning wars thanks to artisanal firearms. In fact, the 16th century was known as the “Age of the Country at War” in Japan. Interestingly, it was also known as the “Christian century.”

They sure do love guns.

The question remains: how did a world leader in gun production completely abandon the technology? It wasn’t overnight, and the reasoning is complex. By the second decade of the 17th century, however, resistance was brewing. As Perrin writes,

It arose from the discovery that efficient weapons tend to overshadow the men who use them… It was a shock to everyone to find out that a farmer with a gun could kill the toughest samurai so readily.

The Japanese government found itself in a dilemma: guns were potent war machines. As the culture was, and remains, notoriously independent, being able to fend off invaders was important. They didn’t want foreigners spreading religion, and guns were a great deterrence.

A strong warrior class—one later epitomized in the classic Kurosawa movies that would inspire “Star Wars,” Bruce Lee, an entire planet to the martial arts and sci-fi mythology—found itself losing something primal: the samurai ethics that maintained a high degree of honor and decorum. They were fighters, and they fought in arm-to-arm combat, not across distances.

Beyond being a weapon, the sword was a metaphor for aesthetics. As Perrin writes, wielding a samurai sword was associated with elegant body movement.

A sword simply is a more graceful weapon to use than a gun, in any time or country. This is why an extended scene of swordplay can appear in a contemporary movie, and be a kind of danger-laden ballet, while a scene of extended gunplay comes out as raw violence.

Remember, his book predates “The Matrix” by a generation. Even still, the unrealistic special effects of firearms will never match the elegance and fluidity of swordsmanship.

I discovered Perrin when reading James Hillman’s 2004 book, A Terrible Love of War. The late psychologist sums up the idea:

It is more important for a person to maintain the aesthetic principles that hold the internal strength of the body’s force in harmonious balance by posture, place of hands, elbows, and legs than to lose this for the sake of the practicality of guns.

I know we’re talking about guns here—as well as the argument that power comes from the barrel of a loaded gun, as is often made by Americans—but don’t think that aesthetics are irrelevant to evolution.

Beauty is also a driver.

A brief diversion

Instead of blindly championing On the Origin of Man, the ornithologist and head curator at Yale University, Richard Prum, reminds us about the third work of Darwin’s series on evolution, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Darwin gave equal weight to beauty as an evolutionary force as he did to power and the survival instinct. In The Evolution of Beauty, Prum writes,

Aesthetic evolution by mate choice is an idea so dangerous that it had to be laundered out of Darwinism itself in order to serve the omnipotence of the explanatory power of natural selection. Only when Darwin’s aesthetic view of evolution is restored to the biological and cultural mainstream will we have a science capable of explaining the diversity of beauty in nature.

Why has this facet of Darwin’s work largely gone unnoticed? Probably for a similar reason that you’ve likely never heard the story of Japan giving up guns for two centuries: men have been writing the history, just as they’ve been doing the science, at least until recently.

The story of raw, sheer power, like that expressed by a gun, fits that narrative better.

Back to the guns

Elegance was not the only reason that the Japanese forfeited firearms. As mentioned, the government didn’t like the fact that farmers were now mowing down samurais—or threatening their power. Legislation began early: beginning in 1607, citizens could only purchase guns from a centralized government.

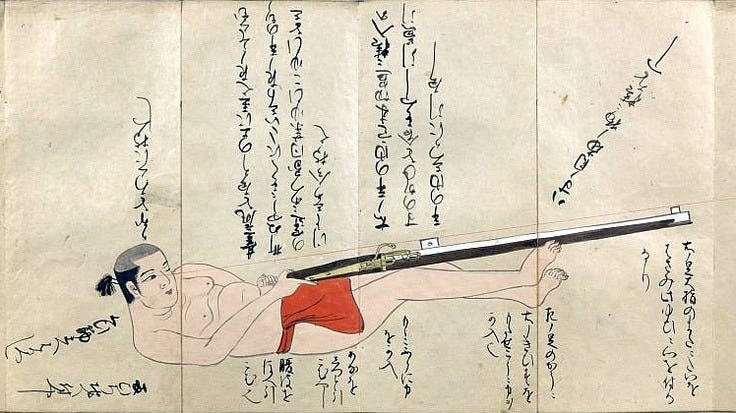

The Japanese generally loathed foreign ideas. This extended to religion as much as weaponry. The symbolism of the sword simply held too much sway. One-third of Perrin’s book is devoted to graphic plates, many featuring the awkward positions of Japanese trying to shoot guns, holding them with their feet, perched on an elbow, a variety of impossible contortions.

And yet, though they knew their power, guns began to fade in 1603. It began when Japan’s regent, Lord Hideyoshi, required all of the region’s citizens to “donate” their guns and swords so his administration could build a gigantic Buddha statue—it was going to be twice the size of the Statue of Liberty. It was his ingenious and crafty way of disarming the peasant class. And it worked.

The last serious battle involving guns in Japan occurred in 1637, 20 years after Christian missionaries were expelled from the country. Still, this “last gasp of Christianity” was won by Japanese guns. Landless samurai had been earlier converted to Christianity and were ready to take territory by force. They failed, and for the next 200 years, the Japanese rid themselves of guns entirely, so much so that the sight of firearms sickened them.

Guns represented everything they detested: undeserved power, foreign occupation, religious zealotry, and, perhaps worst of all, inelegance.

Where do we go from here?

The journalist Chris Hedges covered wars in the Balkans and the Middle East for the NY Times, NPR, Christian Science Monitor, and other news outlets for decades. In 2002, he published War is a Force That Gives Us Meaning. Having returned to America from overseas, he wrote,

Like every recovering addict there is a part of me that remains nostalgic for war’s simplicity and high, even as I cope with the scars it has left behind, mourn the deaths of those I worked with, and struggle with the bestiality I would have been better off not witnessing. There is a part of me—maybe it is a part of many of us—that decided at certain moments that I would rather die like this than go back to the routine of life. The chance to exist for an intense and overpowering moment, even if it meant certain oblivion, seemed worth it in the midst of war—and very stupid once the war ended.

As Hedges knows, war truly seems inescapable given its persistence and reliability. Remember, Darwin noting that beauty is a driver of evolution does not negate the fact that so is survival, which requires power. Both are part of who we are.

Sebastian Junger also spent time embedded with troops, most famously in the harrowing documentary film, “Restrepo.” In his 2016 book, Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging, he writes,

If war were purely and absolutely bad in every single aspect and toxic in all its effects, it would probably not happen as often as it does. But in addition to all the destruction and loss of life, war also inspires ancient human virtues of courage, loyalty, and selflessness that can be utterly intoxicating to the people who experience them.

I’ve read a number of books on war, and the psychology behind warfare, because you can’t separate it from my field of study: religion. You can’t really separate war from anything, as the authors I’ve cited above repeatedly point out.

But Junger makes another relevant point: a society that can’t differentiate between levels of trauma is a failing society. There’s a big difference between PTSD suffered on the battlefield and feelings being hurt on Twitter. He points out that social resilience is a better predictor of overcoming trauma than most anything else.

This is important given the fractured nature of our social discourse, which either takes place on or is fueled by social media. Gun control is a nuanced topic that’s often co-opted by opposing forces making unrealistic claims and demands.

In that light, let’s quote Junger once more, writing about his recurring returns to America from war zones:

First there is a kind of shock at the level of comfort and affluence that we enjoy, but that is followed by the dismal realization that we live in a society that is basically at war with itself. People speak with incredible contempt about—depending on their views—the rich, the poor, the educated, the foreign-born, the president, or the entire US government. It’s a level of contempt that’s usually reserved for enemies in wartime, except that now it’s applied to our fellow citizens. Unlike criticism, contempt is particularly toxic because it assumes a moral superiority in the speaker… People who speak with contempt for one another will probably not remain united for long.

I’ve long wondered: what is the real existential threat that we need to arm ourselves against, the reason citizens need multiple assault weapons? Because there are existential threats in this world: climate change, supply chain crises, poverty, foreign nations that wouldn’t mind seeing an empire crumble. I’m not a violent person and I don’t condone gun worship, but I can also recognize why Gandhi said that sometimes violence is necessary. You don’t always have a choice.

And yet, we do. What surprises me about this gun “debate” is the entwined call for real masculinity—at least in the wellness and libertarian spaces we cover on Conspirituality. It’s even funnier when it comes from the MMA wing of gun worshippers who praise physical strength above all else. Why those who fawn over the elegance of bodily power would choose to worship the most inelegant weapon possible is beyond me.

I don’t really expect America to give up its guns. Yet the fact that sensible regulations—raising the legal age to purchase a gun, closing loopholes, requiring more thorough background checks, and limiting or banning the sales of assault weapons—are mixed in with “they’re coming for our guns!” is absurd. This is exactly what drives contempt: an existential threat, however imagined, to your survival, which drives festishization of the weapon you believe will prolong it.

Asking a Christian society to disarm is even more unrealistic. And yes, Christians did return to Japan, and yes, to protect themselves from foreign influence, the Japanese took up guns again in the late 19th century. Today, however, a country of 127 million people suffers less than 10 gun deaths every year.

If Japanese people want to own a gun, they must attend an all-day class, pass a written test, and achieve at least 95% accuracy during a shooting-range test. Then they have to pass a mental-health evaluation, which takes place at a hospital, and pass a background check, in which the government digs into their criminal record and interviews friends and family. They can only buy shotguns and air rifles — no handguns — and every three years they must retake the class and initial exam.

Gun owners in America often talk about the necessity of hard work. I wonder why that doesn’t extend to the work it takes to be a responsible gun owner.

Discussing the increasing prevalence of computers and other technologies, Perrin reminds us that two steps back can result in a giant leap forward. He closes his investigation by writing,

This is to talk as if progress—however one defines that elusive concept—were something semidivine, an inexorable force outside human control. And, of course, it isn’t. Men can choose to return to remember; they can also choose to forget.

What a powerful, and elegant, solution.

This essay was adapted from Conspirituality: Giving Up the Gun.

This didn’t age very well, did it? 😂 #ShinzoAbe

Americans: never turn them in.